As an artist living in the French Pyrenean mountains, I have been working for the past few years on the cross-border paths from France to Spain. I am interested in the imprint of memory on the landscape and how walking can reactivate memory. My artistic work deals mainly with the paths of exile between France and Spain. The paths were used during the Second World War when escapees fled the Nazi regime. However, thousands crossed over the mountains the opposite way, during the Retirada, when Franco’s army moved into Cataluña and defeated the Republicans. I have been working with a Spanish lady, Teresa, who crossed over the border with her mother and her brother in 1939 at the age of eleven. I shall discuss the artwork that resulted from our talks and which consists in four black and white photographs of the soles of her feet covered in her hand-written testimony.

I shall interrogate the relationship between writing, walking, the feet and the path, and how this connection relates to memory. First, I shall analyse the choice of the feet and question what the sole of the foot means to us, and how it relates to the path. I shall then focus on testimony and on how handwriting can be linked to walking. Finally, I shall question my own use of the technique of overlaying in the photographic image and how this particular artistic practice in which the writing is superimposed onto the images of the feet, reveals the memory of Teresa’s journey across the Pyrenean mountains.

The Feet: The Soles Remember the Path

Foot: n. The lower extremity of the leg below the ankle, on which a person stands or walks.

Oxford Dictionary

Our feet support the weight of our entire body; they enable us to move through space: to walk, dance, run, jump or climb. However, we did not always walk. Not only, as new-borns, did we frantically kick our feet in the air and curl up our toes – proof that our feet, just like our hands are extremely sensitive parts of our body – we also learned to walk over a period of thousands of years. Our feet were equal to our hands until we finally stood up as Homo erectus. The feet remember much more than we imagine. Some one-armed or armless people make extremely good use of their feet – some are marvellous artists, being capable of holding a paintbrush, a pencil between their toes, or modelling clay with the soles and toes of their feet. Our feet are also capable of much more than we think: they do not only carry us; they are agile and highly sensitive. Just like our fingers, the sole of our foot is extremely sensitive to touch and this is because of a high concentration of nerve endings. Not only are they highly sensitive to touch; they are equally responsive to the surface we move along.

Teresa, a close member of my family, walked from Spain to France overnight, crossing over the mountains at the age of eleven. Of all the events she recalled, I believed the most important was what her feet remembered. The wearing of shoes was introduced in early human history so the soles of our feet would be protected against uncomfortable or harmful surfaces, for instance stones, thorns, grit or glass. However, Teresa took her shoes off, for the pain she was experiencing was unbearable. Whereas, we might go for a leisurely hike in the mountains with an expensive pair of hi-tech walking boots, Teresa and her family fled during the night when their guide unexpectedly called them to cross over to France, wearing whatever footwear they had on at the time. Teresa’s feet were in such pain; she preferred to walk barefoot, exposing the soles of her feet to the mountain paths. She recalls that the skin on the soles of her feet was so worn away that she couldn’t walk for several days following her escape from Spain. Teresa gave me the impression that the pain in her feet is synonym of the pain of leaving her country. The further she walked away from her Cataluña, as she calls it, the worse her feet got. Teresa recalls how weakened and worn she felt on her arrival in France, her feet having endured hours of strenuous walking. “As soon as we arrived” she recounts, “at last, all went well, and in spite of blistered feet and exhaustion, I thought everything would be fine.”1

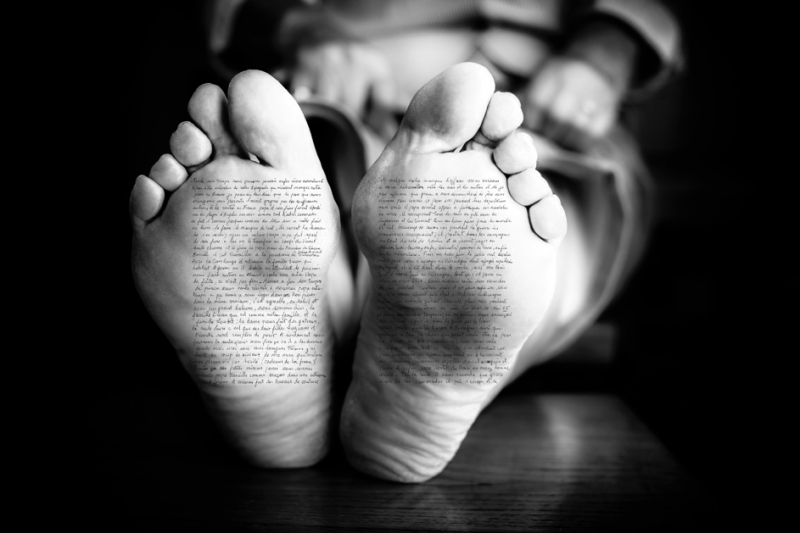

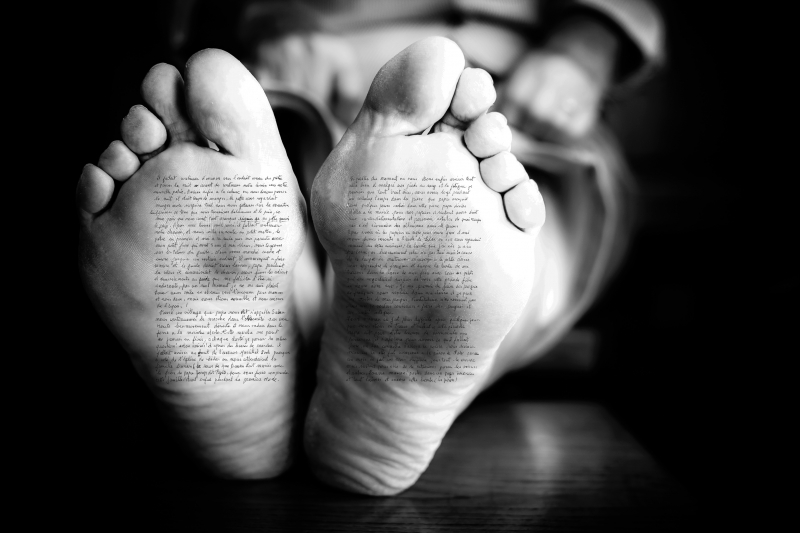

The path led Teresa away from her homeland, and her feet simultaneously carried her along a path that gradually became one of suffering. Therefore, I asked Teresa to sit with her legs upright and to reveal the soles of her feet. The photographs are straightforward, as I have used an evident chiaroscuro so that the white feet stand out on the black background as though they loom up from the dark. In the middle distance, we can tell she’s holding up her trousers. Her hands are firmly gripping the material, which makes her body seem quite tense and rigid. Therefore, her whole posture and her gesture convey uneasiness. She appears as though she is revealing something painful and taboo.

Figure 1

Bridget Sheridan, Teresa, 11 Years Old, Digital print on fine art paper (series of 4), 40cm x 60cm, 2015.

©Bridget Sheridan.

We should note that most Republican exiles living out of or in Spain would not mention their story. It was hushed and kept secret. The taboo travelled down through several generations as Franco was still in power until 1970 and the nationalist movement maintained its strength throughout the 70s. Recently, mentalities have changed and families are starting to clear the air and talk about matters that have been buried deep down in their hearts. Teresa’s story is one of exile, which belongs to the path and to the feet. Both entertain a contiguous relationship: on the one hand the feet leave a trail behind them on the ground as they participate in creating the path, and on the other, the feet remember the contact with the ground.

French philosopher Pierre Sansot believes that paths exist because we have the faculty to embrace the footsteps of others who walked before us and who walk beside us.2 Those who walked before us show us the way. Thus, Teresa is showing us the way. We walk with her and we walk along the path – one of exile. Sansot reminds us that each time that history trembles, Man sets out on foot, each time more eager than the previous. He evokes 1940, when thousands of French people inundated the roads leading from the North of France to the free zone in the South during forty days.3 Walking a path is walking beside others, whether the person is physically present or whether we are following another’s footsteps. French anthropologist David Le Breton notes that the path resembles a scar in the landscape that Man leaves behind him:

Paths [are] memory carved into the earth, trails amongst the veins that run along the ground left by the countless walkers who haunt places throughout Time, a kind of solidarity that has developed between Man and the landscape.4

Again, he evokes memory when he states that:

The walker can feel the earth under his feet as he enters a lively relationship with the path in which his senses are open and his body is available; he develops a memorial connection with the numerous happenings of his journey.5

Le Breton points out how much our body is stimulated during the walk. He also shows that memory not only seeps into the path after the passing of Man, but also how much our body remembers the journey, and our feet in particular.

Teresa’s feet remember the crossing of the Pyrenees. If we take a look at her feet, they are clearly not those of an eleven-year-old, like in the title Teresa, 11 years old. The feet are riddled with wrinkles and her toes show the signs of aging. The skin seems tough and dry – this is clear evidence of a life-long contact with the ground. The soles of her feet reveal the path of life. Thus, there is a gap between the age in the title and the evident age of the lady in the photographs. This creates an effect of nostalgia, as if she is looking back at her previous life in Cataluña.

It is as though Theresa is revealing what she has kept hidden for all this time: her testimony.

The Testimony: Her Hand Walks Along the Path

Teresa produced a notebook. She had in fact written the story of her crossing. “It was for my children,” she told me, “so they know how terrible it was for us.” The last few lines concluded: “My dear children, please bear in mind that war is a terrible thing.” Following the testimony of her exile, and with the current context of war, I knew how cruel Mankind could be. Teresa’s story is universal; her words echo the words of millions of refugees:

Go and fetch your mother and your brother and tell them to hurry without being noticed. It’s the right time. Don’t weigh yourselves down, leave your bags, and just take a couple of things. So there we were, on our way, as though we were going for a stroll, the man in front and us a little way back, scared of being seen.

Eight pages of hand-written words tell the story of an eleven-year-old girl who was torn away from her friends and family. Teresa had chosen to narrate her journey in French, in this way her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren could read her testimony. The writing was simple and direct; therefore, one could almost hear her voice whilst reading the text. She had sat down, alone, to travel once more the paths of her memory, in order that her descendants should know how traumatising such an experience can be and how much that crossing had meant to her. Her hand had travelled along the piece of paper just as her feet had travelled along the mountain paths.

The use of handwritten testimonies is recurrent in my artwork. Handwriting differs from print in that it is mainly to do with the gestural and the movement of the hand. British anthropologist Tim Ingold, in his Brief History of Lines, draws a parallel between writing and walking. There are two points to be made about reading handwriting: firstly, we can almost hear the voice of the writer, and secondly, we follow a trail. Ingold believes that, in the Middle Ages, those who read the Bible had the impression they were listening to the voices of the scriptures. This is because it was believed that the scribe would be directly writing down what he heard from the prophet’s mouth. Therefore, there was a direct connection. Throughout the history of writing, this impression will stay with us. When reading handwritten letters from friends and relatives, we still can almost feel them sitting next to us as we travel along their lines of handwriting. Ingold notes that: “To read a manuscript, as we have seen, is to follow the trails laid down by a hand that joins with the voice in pronouncing the words of a text. But there are no trails to follow on the page of print.”6

The trails Ingold is referring to are the lines of ink left by the tip of the pen as the hand moves across the surface of the paper. The movement is a continuous flow while the nib presses on the paper to release the ink and then rises in turn. This movement was called the ductus, meaning “a leading”, from duct, “course” or “direction” in Latin. Thus, considering Teresa’s testimony, we can admit that her handwriting is leading us somewhere. Handwriting is organic: it draws curves, it trembles, it makes its way up and down, to and fro, while it travels in one direction across the sheet of paper. Teresa leads us along her path of writing. She is our guide.

Rebecca Solnit, who has studied walking in her book Wanderlust, believes that writing a story is similar to walking. She pictures the author as a guide: “To write is to carve a new path through the terrain of the imagination, or to point out new features on a familiar route. To read is to travel through that terrain with the author as guide.”7

If we consider the etymology of the term “story,” “a connected account or narration of some happening” or “a recital of true events,”8 then Teresa’s account of her crossing fits the true meaning of “story.” We must bear in mind that story and history were not differentiated until the 16th century.

Walking and handwriting are similar in the ways that they are both linked to movement and tracing lines, that they both leave trails, and that there is an idea of direction and leading one somewhere. They are both singular too.

What exactly happens when the artist superimposes writing on the skin? Can we evoke a veil or an imprint? And furthermore, does it convey the idea of memory?

Photography and Writing: Overlaying the Paths of Memory

Teresa’s writing has been cut out of the original image and I have used the overlay tool to blend the two layers: the photograph of the feet and the scan of Teresa’s writing. Working with layers is significant as we are dealing with memory. However, I work in France and I mainly use the word incrustation, which I find even more relevant in this case. The word comes from the latin crūsta, “crust,” “shell,” “bark,” “that which has been hardened.” So basically, incruster would mean, “to insert into a hard or a tough surface.” We can hardly imagine a digital photograph having any physical texture until it is printed onto a surface. Nevertheless, what is in the image, Teresa’s feet, do have a texture, and I previously noted that they are tough and hardened with age and this is visible in the photograph. Using this technique is inserting or inlaying the writing in Teresa’s skin; it becomes part of her body. Therefore, the feet bear the traces of the journey, as if they had been tattooed with the ink of her pen. Time has set her testimony in the soles of her feet.

The feet are also open like the pages of a book: four photographs, eight pages. Each page of writing has kept its original layout and has been layered on the sole of each foot. Thus, the soles of Teresa’s feet also resemble sheets of paper.

Tim Ingold believes that:

The past, in short, does not tail off like a succession of dots left ever further behind. Such a tail is but the ghost of history retrospectively, reconstructed as a sequence of unique events. In reality, the past is with us as we press into the future. In this pressure lies the work of memory, the guiding hand of consciousness that, as it goes along, also remembers the way. Retracing the lines of past lives is the way we proceed along our own.9

These lines can be seen as those that run along Teresa’s skin in the photographs. Here, the handwriting is obviously that of an elderly person, hesitant and squiggly. Thus, the sinuous lines on the souls of her feet tell the story of an aged lady, travelling the paths of her memory:

We had to move on to the place the shepherd knew of and spend the night there before making our way towards our new homeland. It was time to eat when we came to the hut where we were to spend the night. The shepherd watched us eat and was astonished at the way we dived on the food. […] We walked on and on to some place, it was starting to get dark and the guide had to leave us here. […] We said goodbye and thanks the guide who, in turn, congratulated me on how resilient I was, not once did I complain. So there we were, on our way to the unknown, my mother and us two, but we were together and we had hope! […] After a village that papa said was Salau, we walked on in the dark, fortunately for us on an empty road, and hid in the ditch at the slightest alert.

The vocabulary Teresa uses evokes the journey, the walk and movement. Thereupon, the ink flows from her pen, spilling words of pain and exile. These same words are then superimposed on the soles of her feet.

The photograph becomes the surface where the lines materialize; it redoubles the skin. It becomes a surface made of written lines, which the viewer can travel along. It becomes the doorway between interior and exterior, just like the skin acts as an envelope round our body. Lines such as cracks, wrinkles, scars and folds cover the exterior of our body, whereas violet and blue veins show like watermarks underneath the skin. Bearing in mind that the skin acts as a sensitive memory of our lives, overlaying the written lines of travel on the skin makes sense.

To conclude, we can say that the photographs of Teresa’s feet truly evoke her past. Her feet not only carried her entire body over the Pyrenees, bearing the imprint of the ground on the soles of these, they also carried her through life. Her hand-written testimony is one of pain, but also one of nostalgia; she is travelling once more along the paths of her memory, back to the homeland she left as a child.

The photograph becomes the doorway between her interior, her hidden memories which stayed taboo for many years and the exterior. She presents her feet and her testimony for us to travel along the paths of memory with her, bringing to life her own story, but not only. Teresa’s testimony brings to mind the sad story of many people, past and present: one of exile.